Slavery’s Legacies

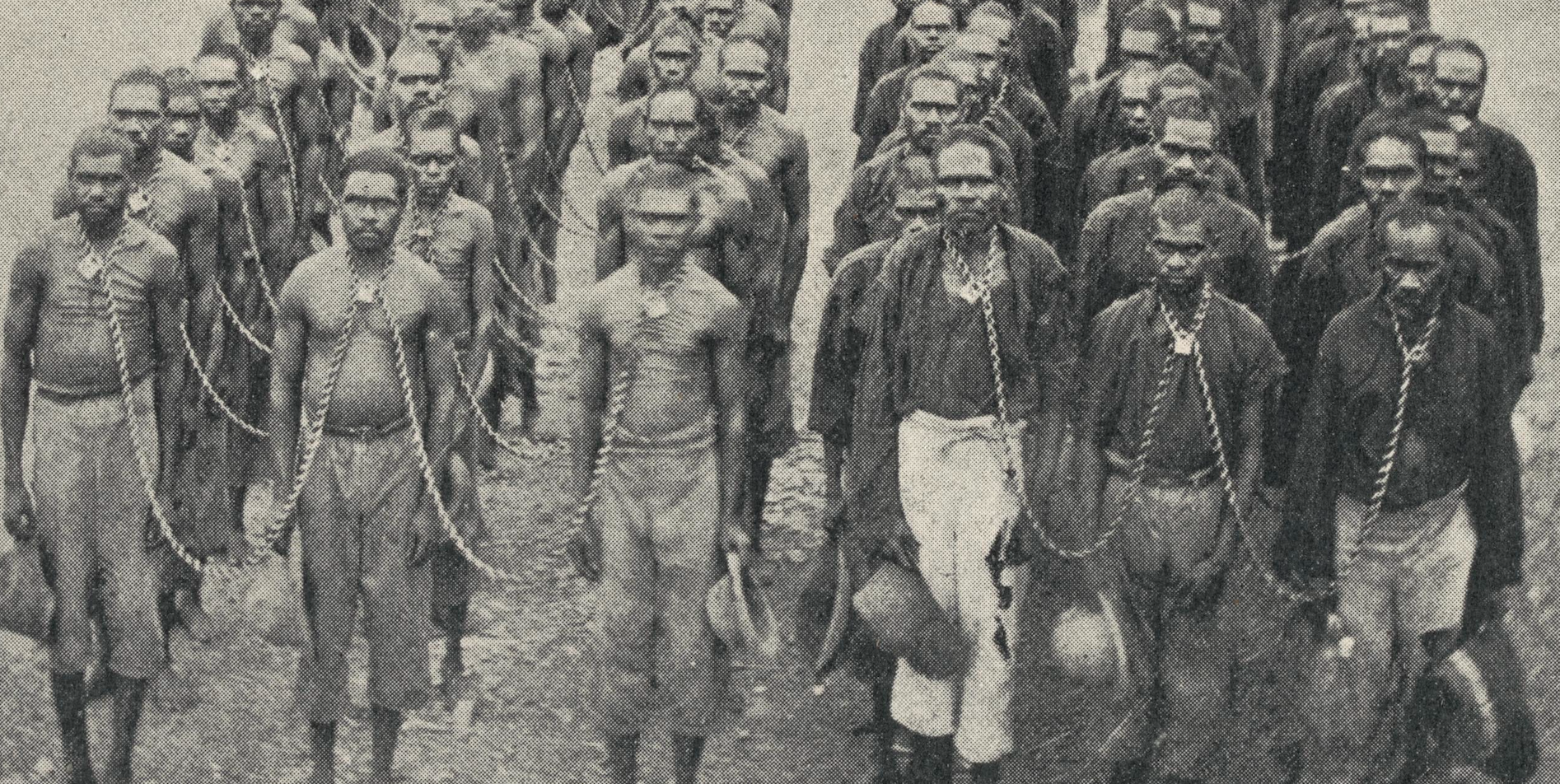

‘Aboriginal bathing gang’, ‘The Aborigines question’, The Western Mail, illustrated supplement, 18 February 1905, p. 24.

This image is taken from a newspaper feature published in 1905 and shows an ‘Aboriginal bathing gang’, at Wyndham, north-western Western Australia. While it seems so shocking to us now as evidence of colonial injustice and brutality, at the time this was published many observers regarded the image as proof of the prisoners’ humane treatment. Humanitarians drew on British anti-slavery discourse to protest against Aboriginal neck-chaining. Today, Aboriginal communities from the Kimberley advise that they wish these difficult stories to be told.

From 1836, the colonial invasion and pastoral occupation of south-eastern Australia accelerated as never before. This project aims to explore how this dramatic land grab was connected to Britain’s simultaneous abolition of slavery from 1833.

By mid-century, colonisers in the east had seized Indigenous lands that stretched from Rockhampton in Queensland to South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula, on which they ran their flocks and herds. The proposed project will trace the flow and impact of capital, people and culture connected with slavery, from Britain and the British Caribbean to Australia. It will focus on the two colonial settlements established simultaneously in the immediate aftermath of abolition, South Australia and the Port Phillip District. Both were fuelled by a significant portion of the £20 million in ‘compensation’ paid by British taxpayers to former slave-owners for the loss of their human ‘property’. From 1834, colonisers from Van Diemen’s Land crossed Bass Strait to occupy territory formally recognised by the British in 1836 as the ‘Port Phillip District of New South Wales’. By placing the dispossession and exploitation of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia within a wider imperial and global context this project aims to offer a new way of understanding Australia’s colonial history.

Charles Bruce (engraver) after Robert Neill (attrib.), Hobart Town Chain Gang, c.1831, copperplate engraving, in James Backhouse, (1843). A narrative of a visit to the Australian colonies (London: Hamilton, Adams, 1843). Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, call no PIC Volume 9 #NK3894

Overlooked Histories of Slavery

The project asks:

How important was the legacy of British slavery for the colonisation of South Australia and the Port Phillip District (Victoria), why has it been overlooked, and how can it inform new histories of Australia?

After emancipation in the 1830s, what routes did people and capital involved in slavery follow to South Australia and the Port Phillip District? How did these two colonies differ and what did they share?

How did principles and practices drawn from Britain’s system of slavery – especially relating to land commodification, mercantilism, labour and the treatment of colonised peoples – shape the new settlements?

South Australia and the Port Phillip District were both established immediately after abolition with significant slavery compensation funding. Settlers in each colony benefited from substantial slavery compensation awards: the Legacies of British Slave-ownership (LBS) database records 24 individuals (and 60 separate records) linked to South Australia, while Victoria was associated with 100 individuals (and 205 records). Our own recent research indicates that many more such links exist outside the LBS, including via offshore British investors who used agents to oversee their Australian interests.

Britain’s South Australia Act (1834) required £45K of land to be sold to intending immigrants before colonisation could commence, in a new colonial model that combined Crown governance with privatised control of land. Such ‘systematic colonisation’, as envisaged by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, was predicated on unfettered access to land, in the first instance the Country of the Kaurna people along St Vincent Gulf. Colonisers promised to recognise Indigenous rights, but ignored them in practice: the Aboriginal peoples of SA were soon forced to resist violence, dispossession and exploitation. Systematic colonisation gained popularity at the time of slavery’s abolition not least because it provided alternative opportunities for colonial investment and profit, and explicitly sought to replace slavery with ‘free’ labour. Compensation paid under the 1833 Abolition Act was invested directly into South Australian land purchases; four of the nine Colonization Commissioners appointed in 1835 were significant slavery beneficiaries. Significant numbers of settlers were both awardees (or their close relatives) and enthusiastic Wakefieldians

The sustained colonial invasion of the Port Phillip District began when colonisers from Van Diemen’s Land established themselves on Gunditjmara land at Portland Bay in 1834 and then, from June 1835, on Kulin lands surrounding Port Phillip Bay. Violent and devastating conflict ensued: in the Port Phillip District, the combined effects of violence, disease and alienation reduced the Aboriginal population by an estimated 80% in under 20 years. Important pastoral ventures, including Niel Black & Co (est. 1839) and the Clyde Company (est. 1836), derived capital from the business of slavery, while some of Britain’s most prosperous mercantile houses extended their operations from the Atlantic to Melbourne. Leading civil servants, including governors Barkly, Darling and Manners-Sutton, and Supreme Court judge, Edward Eyre Williams, also had strong financial and professional connections to Britain’s Caribbean colonies.